Soaring electricity rates threaten climate action

Households may balk at joining the energy transition unless policymakers in California and beyond act to rein in electricity rate increases.

Quitting Carbon is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or making a one-time donation.

“What I wanted to do is blow the whistle on this.”

So, U.S. Senator Ron Wyden (D) told reporters last month. “This” is a reference to soaring electricity rates in the service territory of Portland General Electric (PGE), Oregon’s largest investor-owned electric utility.

Wyden’s session with reporters was in response to a November 25 letter he sent to Maria Pope, PGE’s CEO, calling out recent rate increases that have left customers paying 41% more for their electric than they did four years ago.

PGE has increased rates, on average, by 11% in 2022, 7% in 2023, and 18% in 2024, and is asking the Oregon Public Utilities Commission to approve a 7.3% increase for 2025, Alex Baumhardt reported for the Oregon Capital Chronicle.

“The people I’m hearing from are balancing the food bill, against the rent bill, against the gas bill, and there’s another PGE rate hike, apparently, on offer right now, and folks are telling me this is not sustainable,” Wyden told reporters. “After 41%, it’s time to take a timeout and give a break to the ratepayer.”

Soaring rates in California

In California, soaring electricity prices are an even bigger issue – and, left unaddressed, could hinder the state’s ability to achieve its climate goals.

When I started writing about California energy policy two decades ago, the common refrain, when policymakers were pressed by reporters or advocates about California’s then-high electricity rates, was: focus on utility bills, not on rates.

And until recently, that was reasonable advice.

Beginning in the 1970s, with the establishment of the California Energy Commission (CEC) and the pioneering research by the late energy efficiency champion Art Rosenfeld, the Golden State became a world leader in energy efficiency.

California policymakers developed a system of R&D programs and standards – including Title 24, the best energy efficiency standards program for buildings in the country – that almost single-handedly created a national market for high-efficiency refrigerators, lighting, and other household appliances.

All that effort held utility bills in check, even as electricity rates in California remained above the national average.

Exacerbated by climate change

But in the years ahead, power demand is expected to increase in California as buildings and vehicles transition from fossil fuels to carbon-free electricity as part of the state’s push to achieve carbon neutrality by 2045. Climate change makes the job even tougher.

Even erstwhile temperate coastal cities like San Francisco and Los Angeles now experience stifling heat waves. And northern cities like Sacramento, Chico, and Redding regularly top 100˚F (38˚C) in summer. Millions of households across the state are either using electricity to cool their homes for the first time or using much more electricity than they did previously to keep their homes comfortable.

If electricity rates keep rising faster than inflation, as they have over the past decade in California, potentially life-saving summer cooling could become prohibitively expensive, especially for low-income households that use conventional air-conditioners rather than heat pumps to keep cool.

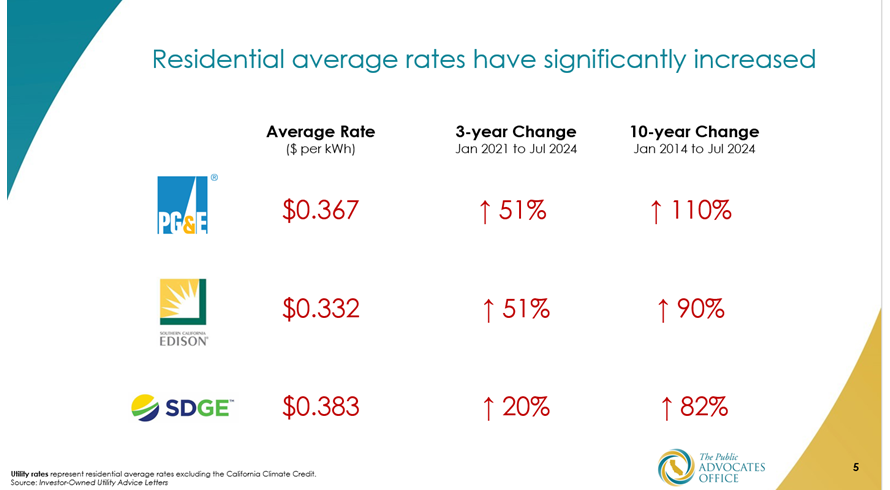

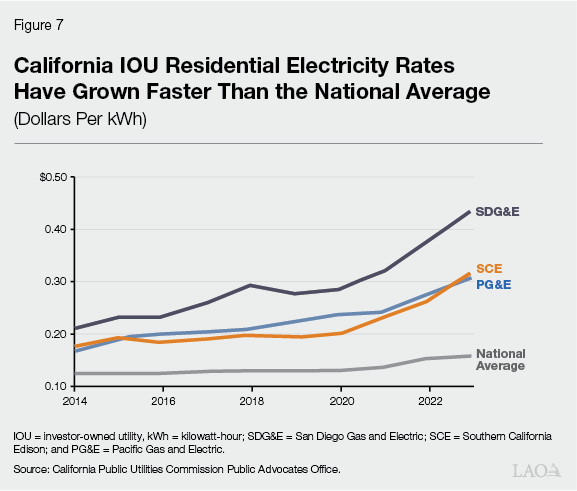

The average residential price of electricity in California (31.64 cents per kilowatt-hour) is already nearly two times the national average (16.83¢/kWh), according to the latest data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) has increased its rates four times in 2024 alone. Nearly 1 in 5 California households are behind on their energy bills, according to the Public Advocates Office at the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC).

Status quo not tenable

Democratic leaders in the California Legislature signaled this week that the status quo is not tenable.

“California has always led the way on climate. And we will continue to lead on climate. But not on the backs of poor and working people, not with taxes or fees for programs that don’t work, and not by blocking housing and critical infrastructure projects,” Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas said Monday in opening remarks at a special session of the Legislature convened by Gov. Gavin Newsom (D).

“This Senate must double down on our efforts to make life more affordable and livable, make our economy work for all, and not just a privileged few,” Senate leader Mike McGuire said in his opening remarks.

It’s a big and complicated problem. Myriad factors* have sent electricity rates soaring in California, including expensive legacy renewables procurements, an unwillingness by commissioners at the CPUC to push back on rate increases proposed by the state’s largest utilities, transmission and distribution upgrades, and investments to prevent wildfires.

CalMatters’ Alejandro Lazo reported this week that the CPUC authorized the state’s three investor-owned utilities – San Diego Gas and Electric (SDG&E), Southern California Edison (SCE), and PG&E – to collect $27 billion in wildfire prevention and insurance costs from ratepayers from 2019-2023.

Solutions lacking

Thus far, the solutions proposed by California lawmakers to make electricity more affordable – including a gimmicky one-time bill credit of between $30 to $70 floated earlier this fall – have not been commensurate to the challenge.

Newsom issued an executive order on October 30 that directed the CEC and CPUC to examine all the electric ratepayer-supported programs they oversee and report back by January 1, 2025, on those “that may be unduly adding to rates.”

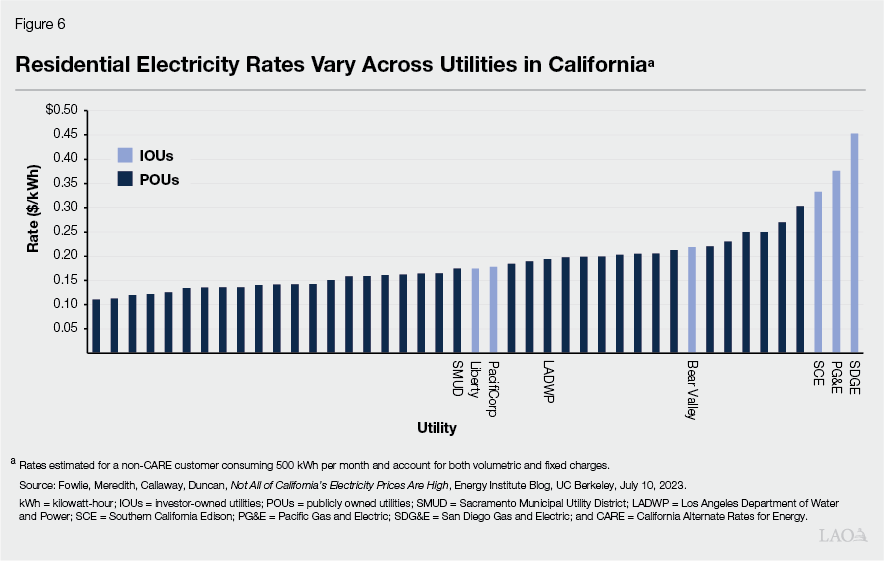

I’ll note here, by the way, that the 2023 average residential price of electricity at large publicly owned, not-for-profit California utilities like the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (22.99¢/kWh) and the Sacramento Municipal Utility District (16.89¢/kWh) was significantly less than it was at the for-profit giants SDG&E (45.48¢/kWh), SCE (32.33¢/kWh), and PG&E (34.04¢/kWh), according to the EIA.

The path forward

California policymakers need to find ways to shift more of the financial burden for public goods like wildfire prevention, low-income customer bill assistance, energy efficiency programs, and electric vehicle charging infrastructure to those most able to pay by funding these critical investments in the state’s general budget, and not on utility bills.

The German government, for instance, eliminated the renewable energy surcharge on utility bills that had been used to pay solar and wind power plant operators for power sent to the grid and now covers the cost of these feed-in tariff payments via the country’s general budget. Danish lawmakers have reduced the country’s electricity tax in recent years to lower the cost of energy but also to give households an incentive to switch to renewable electricity.

California’s political leaders are asking the state’s residents to shift their homes and vehicles to run on clean electricity to help the state achieve carbon neutrality over the next two decades – as they should. But if they don’t succeed in curbing electricity rate increases that outpace inflation, Californians may balk at joining the energy transition.

It’s clear that the current trajectory is, as Sen. Wyden noted, not sustainable.

*I purposely left the fraught topic of rooftop solar incentives’ contribution to California’s recent electricity rate increases out of this column. It’s a topic I’ll return to later. I will note, however, that research published last month by M.Cubed Consulting (commissioned by the California Solar and Storage Association) found that rooftop solar would save California utility customers $2.3 billion in 2024, not impose a $8.5 billion cost shift on non-solar customers, as reported by Canary Media’s Jeff St. John.